Tr20

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tr20-59, photographed at the Factory

photo of a Pershing class locomotive; National

Railroad Museum (USA) collection. For

comparison: unsuperheated Consolidation built for the Railway

Operating Division… …and

modified version supplied to PLM by Montreal Locomotive Works. Both pictures from Train Shed

Cyclopedia

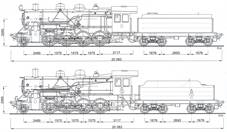

(see References). CFR 140.117, preserved at the Tr20 side drawings by Marek Ćwikła (source: SK

vol.12/2008). Upper drawing shows the original version, lower – with

modifications (Tr20-151 through 175). Ex-USATC

649, operated by Texas State Railroad.

Photo by Gary Snook (courtesy Chaz Robitaille). Preserved No. 101 at the National Railroad Museum, Green Bay, USA. Photo taken on April

17, 2011, by Hugh Llewellyn (source: www.commons.wikimedia.org). Administration

des chemins de fer d'Alsace et de Lorraine

initially retained pre-war Prussian-type designation system, hence Pershings were

classed G14. This example, G14 5745, survived until nationalization in 1938

and later became SNCF 140B-745.

Source: Dampflokomotiven – Bahnen in Elsass-Lothringen (see References). ‘Pershings’

prepared for shipment to Europe; location and date unknown. Source: The Locomotives that Baldwin Built

(see References). |

After

WWI Polish railways took over a number of German, Austrian and Russian

locomotives, but most of them were old and obsolete engines running on

saturated steam. Those suitable for heavy freight traffic included primarily

Prussian class G10 (re-classed Tw1 in the PKP

service), of which 35 were taken over from KPEV and twenty from Austrian military railways; further thirty

were built by Schwartzkopff

against Polish order. These engines had the tractive effort of 15.2 tonnes. Other types with comparable performance were

usually represented by single examples and indigenous Tr21 (designed in

co-operation with Austrian StEG) appeared only in 1922. Soon it became evident that

coal transportation and export would be of vital importance for national

economy, which obviously resulted in heavy drafts, so there was an urgent

need for a powerful freighter. Brand

new engines could be readily supplied by American manufacturers. Among them, Baldwin

Locomotive Works had already become the largest locomotive builder in the

world. In July 1917, after USA had entered WWI, U.S. Army Transportation

Corps (USATC) placed an order for a simple and reliable engine for use

in Europe. Its design was based on a 1-4-0 (Consolidation) locomotive, factory type 10-36 E, ordered for

British Army (Railway Operating

Division), of which 150 examples were built. Main difference was the

introduction of Schmidt-type superheater: original

British Consolidations ran on

saturated steam. New engine had many European features, in particular cabs,

but generally represented the American design school. Further orders followed

and total output eventually reached about 2000 examples. SK gives

2019, but detailed study of available sources (many thanks to Piotr Staszewski) yields 1915 engines for U.S. Army, 25 for

French government and six for U.S. Navy – 1946 in all. Further 100 similar

locomotives were supplied directly to French Compagnie

de Chemins de Fer de Paris à Lyon et

à la Méditerranée (PLM) by Montreal

Locomotive Works (an ALCO subsidiary). Their steam engine cylinder

bore/piston stroke was 584/660 mm (i.e. 23’/26’), compared with 21’/28’ of

the original Baldwin design, which of course resulted in higher tractive

effort of 15.9 tonnes. They were also slightly

longer and lighter. Due to characteristic boiler shape they were nicknamed

‘Les Bossues’ (humpbacks). In

1918 U.S. Army began referring to their Consolidations

as Pershing class, in honor of Gen. John J. Pershing, the AEF

commander. After the war, the majority of these locomotives – 1816 – went to

various French companies. Apart from PLM, they were used by Alsace-Lorraine

(AL), Est, Etat, Midi,

Nord and Paris-Orléans (PO)

and it seems doubtful whether any was eventually shipped back to the USA

(most probably two engines remained there in the USATC service). Nord acquired also 113 ex-British unsuperheated engines. After various French railway enterprises

were merged into Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer Français (SNCF) in 1938, they continued with

the new company. They were classed 140, but this class included also other

locomotives with the 1-4-0 axle arrangement of French origin. During the war

French engines were scattered throughout the entire part of Europe under

German control. Details are lacking, but according to the monograph by Tomasz

Roszak (see References) over 300 ex-French 140s saw

service with Ostbahn

in Poland. Some of them were not evacuated and were taken over by PKP. In late 1940s over 130 French

140s were awaiting return to their homeland, but no international agreement

was reached and most of them were scrapped in 1950s. A few Pershings from SNCF were briefly used by PKP immediately after the war, but

they were never included in the company’s rosters and retained their wartime

numbers. Very few details on their service are available. Another

recipient of Pershings was Romania. In all,

Romanian railways CFR acquired 65 examples. Of these, 140.101 through

140.115, from wartime Baldwin production, were presented by French

authorities in 1919, together with 48 ex-KPEV engines of various

types. In April 1920, CFR purchased further fifty engines: 140.116

through 140.140 (built by Baldwin) and 140.141 through 140.165 (built

by Montreal Locomotive Works). They differed in having rocking grates

and provisions for mixed coal/oil firing. Apart from five written off after

accidents, all CFR engines were still in service in late 1953. Most were

withdrawn between 1970 and 1973 and the last one was 140.105 (ex USATC

1664, Baldwin 50433/1918), withdrawn in September 1977 and formally

written off in October 1979. Polish

government did not buy surplus U.S. Army engines, although such option was

contemplated. Instead, in July 1919, 150 brand new ones were ordered from Baldwin.

Basically they corresponded to the design developed for USATC. They were supplied in a few batches (serial numbers in the

range from 52421/1919 to 53313/1920) and assembled at the Troyl-Werke

(a division of The International Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. Ltd.)

in Gdańsk, first twelve arriving in December 1919.

Initially they were given service numbers 6001 through 6150; later, in

accordance with new designation system introduced in 1922, they were

re-numbered Tr20-1 through 150. In 1922 additional 25 engines were ordered

and supplied, with serial numbers in the range from 55695/1922 to 55868/1922.

They differed in some details and externally could be distinguished by higher

cabs, extended smokestacks and tenders with higher side walls. Ten were

fitted with steel fireboxes. Due to these differences, the second batch was

initially considered a new class, numerical designations 7001 through 7025

being initially assigned. However, they were finally numbered 6151 through

6175 and later re-numbered Tr20-151 through 175 – according to some sources,

before actual delivery. Baldwin

locomotives, compared to their nearest equivalent then in the PKP

service – the above-mentioned class Tw1 – were only marginally heavier, but

longer by over one metre, mainly due to larger

tender. Smaller cylinder bore was to some extent compensated by higher steam

pressure, but tractive effort was slightly lower, as Tr20 had four coupled

axles instead of five. Maximum axle load was substantially higher, by over

two tonnes. Powerful and robust engines, Tr20s were

accepted by Polish railwaymen with sheer

enthusiasm. Some of them, immediately after delivery, were sent eastwards, as

they were badly needed during the fight against the Bolshevik assault.

Despite harsh conditions, poor water quality and insufficient maintenance

facilities they gave good performance. Tr20s were, however, not entirely

trouble-free. Some items in the driver’s cab obstructed forward view and axle

bearings often overheated. There were several other minor problems, but two

shortcomings were found particularly serious. Fairly soon it was revealed

that rear boiler tube wall was rather weak and prone to distortion and

fatigue cracks. Connection between water box and tender frame was also too

weak, so a head-on collision usually resulted in water box being rammed into

the driver’s cab, which was often fatal for the footplate crew. It seems that

the above-mentioned shortcomings were, at least to some extent, caused by

hurried development and production rather than basic design flaws. First

order from the British Government for 150 engines was placed on July 17 and

completed by October 1, 1917; when hostilities ended in November 1918, Baldwin

were delivering Consolidations for USATC

at the rate of about 300 locomotives per month. Tr20s

were later supplemented by indigenous Tr21s with similar overall

characteristics (tractive effort of 14.4 tonnes

with maximum axle load of 17 tonnes). With gradual

introduction of Ty23s, which soon dominated heavy freight traffic, both these

classes were relegated to secondary lines and later to switching, but most

probably all 175 Tr20s remained in service until 1939. Their good service

during the war against Bolsheviks must have impressed military authorities,

as shortly before WWII it was intended to fit all of them with car heating

installations, so that they could haul military trains (with officers’ cars

usually right behind the engine!). At least two, Tr20-140 and Tr20-154, were

in fact fitted with such installations by Troyl-Werke.

According to LP and SK, which give the most comprehensive

information on individual examples, after the September campaign 98

engines were impressed into DRG as class 5637-38; 66 went

to the Soviet Union and were taken over by NKPS. One (Tr20-36) was

taken to Lithuania, to fall into Soviet hands in 1940. There is no reliable

data on the remaining ten examples, but most probably they were also captured

by the Soviets. Two German engines, badly damaged during hostilities

(Tr20-103 and Tr20-168) were written off in 1940. 59 Soviet engines were

later captured by the Germans and also impressed into the DRG service. In 1940, Polish boiler

works Babcock-Zieleniewski (renamed Ferrum-Werk Sosnowitz)

built seven replacement boilers for Tr20s; they differed in distance between

tube walls shortened by 19 mm (due to tube wall strengthening), which

resulted in heating surface reduction by 1.3 sq.m. After

1945, 88 ex-DRG Tr20s were directly returned to PKP, plus six

more that had seen brief service in Yugoslavia (2) and Austria (4).

Czechoslovakian railways took over six examples, of which three were given ČSD

service numbers: 437.2500 (Tr20-38), 437.2501 (Tr20-83) and 437.2502

(Tr20-125). First was sold to industry in 1958 and second was scrapped in

1961. The remaining three saw no service with ČSD. Two of them,

together with 437.2502, were returned to PKP between 1947 and 1949;

data on the third is lacking. Tr20-145, taken over by Soviet military

authorities in Eastern Germany, but probably not restored in service, was

returned in 1949. Tr20-87, formally taken over by Ostbahn,

but with no service record, was rebuilt from a wreck after the war. The most

mysterious post-war Tr20 is Tr20-99, possibly also taken over as a wreck, but

with unknown identity; formally included in rosters, it saw no service and

was written off in 1951. DB kept 23 Tr20s, scrapped in early 1950s; of

fifteen taken over by DR, all but one were returned in 1955 and

1956, but their condition was very poor and they were scrapped with no new

service numbers assigned. Thus, in

all, 100 Tr20s were given PKP service numbers after WWII, but some

were written off in late 1940s or early 1950s. According to rosters quoted in

SK, this class numbered 88 examples in October 1946, 96 in July 1949

and 86 in January1955. As rapid electrification had been envisaged, Tr20s,

together with other older classes, were intended for rapid withdrawal. These

plans had to be modified fairly soon: 43 Tr20s still remained in service in

early 1965. This engine, however, remained a troublesome one. Boiler material

ageing forced costly repairs and steam engine cylinder fractures were

commonplace. Eight examples survived until 1974 and the last one, Tr20-95

(pre-war Tr20-133, Baldwin 53016/1920), was finally withdrawn in

November. Unfortunately, not even a single example managed to escape the

cutter’s torch. As

far as I know, three Pershings have survived

until today. One engine from the first batch of 150 (USATC No.766, Baldwin

48714/1918), which had not been sent to France, saw service at various army

bases around the USA. Withdrawn in 1945, it was sent to Korea in 1947 along

with 100 engines acquired from Europe – hence its new number, No.101. It was

returned by the authorities of the Korean Republic in 1959 and can now be

seen at the National Railroad Museum,

Green Bay, WN. The second surviving Pershing

is CFR 140.117 (Baldwin 53343/1920), which has been preserved

in Sibiu. It underwent a major overhaul in 2004 and saw some service with

special trains; possibly it is still in working order. Third example is ex-USATC 649 (re-numbered from 396 before

delivery), which never left the USA and initially worked at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Later it was

transferred to Warrier River Terminal Railroad, Alabama, to

be transferred to the Army Corps of

Engineers in late 1930s. Withdrawn from the Claiborne-Polk Military

Railroad in 1946 (No.20), it was sold to Tremont and Gulf Railroad (No.28) and then to Southern Pine Lumber Company. Donated

in 1976 to Texas State Railroad of Rusk, Texas, it was initially placed on

static display. Restored to the working order in 1992 and numbered 300, it

remained operational with tourist trains until 2017. In 2015 the Sothern Pine livery and service number

were restored. Currently this engine is undergoing overhaul. Many thanks to

Chaz Robitaille and Everett Lueck for information

and details! Main technical data

1)

Data in brackets for replacement boilers. 2)

Some sources give ‘rounded-up’ figures: bore 535 mm,

stroke 715 mm. 3)

Refers to Polish order only. List of

vehicles can be found here. References

and acknowledgments

-

Monographic article by Tomasz Roszak

(SK vol. 12/2008); -

Normalnotorowe parowozy amerykańskie na PKP

(Standard-Gauge American Steam

Locomotives of PKP) by the same author (Kolpress, 2014); - LP, ITFR,

RR, EZ vol. 3; - Dampflokomotiven – Bahnen

in Elsass-Lothringen by Lothar Spielhoff (Alba,

1991); -

Private communication: Tamas

Haller (Romania), Robert J. Lettenberger (USA), Tim

Moore (USA), Adrian Raduta (Romania), Chaz

Robitaille (USA) and Everett Lueck (USA); -

Piotr Staszewski (also

private communication – many thanks for very throughout and detailed study on

the production and service of ‘Pershings’, which

allowed me to correct a number of errors in this entry); -

Train

Shed Cyclopedia No. 9: War and Standard Locomotives and Cars (1919);

reprint by Newton K. Gregg (1973). -

The

Locomotives that Baldwin Built by Fred Westing

(Bonanza Books, 1966). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||